Nandita Raman is from Benaras (India) and works with a range of mediums including photography, video, drawing and language. Her work has been exhibited at George Eastman Museum, Museum of Moving Images, Center for Documentary Studies, Duke University and Columbia University. She has curated group exhibitions in New York and Varanasi. Her work has been written about in the New York Times, British Journal of Photography, the Hindu; and published in MIT Press’s Performance Art Journal and Documenta 14 volume titled South As A State Of Mind. She was 2017 Workspace Resident at Baxter St Camera Club of New York and is a recipient of Alkazi Foundation’s Documentary Photography Grant. Nandita is a graduate of the Bard College-International Center of Photography’s MFA program and teaches photography at SUNY Purchase

College.

Spotlight E/Merge artists through brief Q&A Interviews

E/Merge: Art of the Indian Diaspora, the opening exhibition of NIAM’s first brick and mortar home, showcases contemporary, cutting-edge works created by nine emerging Indian-American visual artists from across the United States.

Nandita Raman, who was born in India and lives in New York; she works with a range of mediums, including photography, video, drawing, and language.

What first led you to expressing yourself through visual art?

Visual art—whether it was a drawing, a painting, or later photography—has always have been part of my everyday life. I remember spending weekends drawing as a child. The thing that happens when making visual art is that time feels different: it slows down, giving me a way to reflect on the minute, the day, the year, the world around me, in a way language hasn’t necessarily functioned for me. Although I use writing to work through things as part of my process, using drawings or photography helps me find a way of engaging and making sense of my world.

What inspired the work you chose for NIAM?

When Shaurya Kumar, [E/Merge curator] showed me the layout of the space and the space available to me, I realized it was very specific, with its narrow hallways and walls that almost mirrored each other. That gave me an anchor to start thinking about the work vis a vis the space. The theme—art of the diaspora—is not something I have to think about. That’s the life I live every day, so it’s inherent. After multiple conversations with Shaurya, Body Is A Situation felt like the most suitable work considering the gallery space—it’s so much about journeying, and taking the body’s cues within those journeys, to come to a cultural, social, and political understanding.

Why is it important to you to reflect your combined identity as an Indian and an American?

These identities don’t have a generative place in my life, thinking, and making. Who is an Indian? The Indian that completely disagrees with the political situation in the country right now, or the Indian who loves classical music and the culture of the city I grew up in, but the people don’t have a place for a queer person? And I could ask the same question about which American I am. So, these identities are too simplistic and straight-jacket the rich and complex peoples each of us are and have the potential to be.

What is coming up for you?

I am making a book of my earliest body of work, a set of photographs of single-screen theaters in a few different cities in India. I’m in India for the first quarter of the year to continue working on Body Is A Situation.

Statement

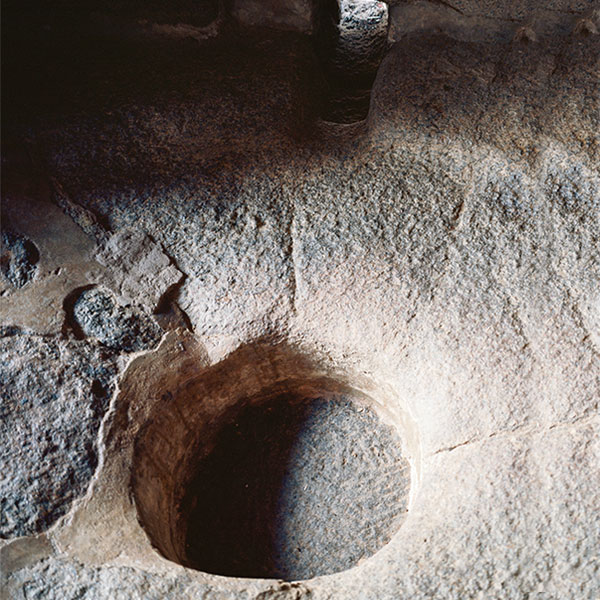

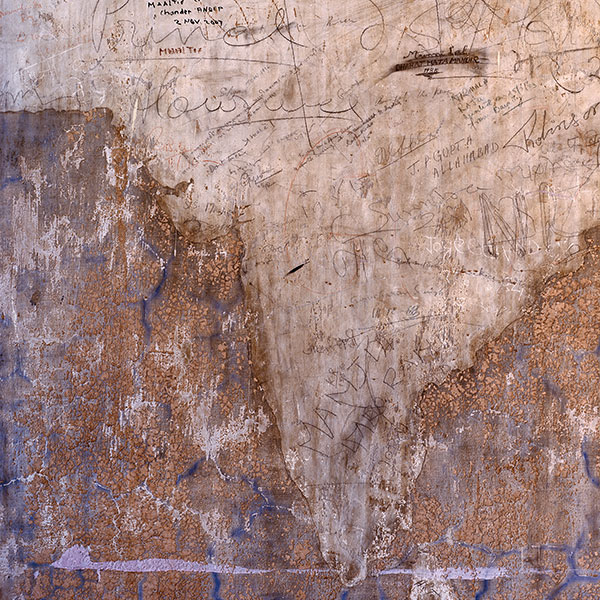

Using my body as a device, Body Is A Situation is a re-looking at the city of Varanasi (Benares) in India, which features prominently in the mystique and map of the East. It examines tropes of representation in the colonial gaze while relying on the body for awareness of place, culture, politics and history. I’m using drawings, etching, photographs and text in this work.

Benares, also my hometown, is a heartland of Hindu and Buddhist religions and a major center for philosophy and pilgrimage. It is deeply rooted in traditions that have twisted into rigid structures with patriarchal overtones. Growing up there, I was inundated with depictions of the city from as early as the 16th century, all of which are consistently devoted to the spectacular riverfront architecture, ‘exotic’ people, and their lives that unfold in public by the river Ganga. In these paintings, lithographs and photographs people feature in a subsidiary role, as a measure of scale in the grand compositions. This aesthetic paradigm of the picturesque, typically assembled by the outsider, is also adopted by the citizen. It disciplines both knowledge and body in specific ways. Photography, like cinema, has always been an intimate companion in travel. Both are recording mediums that describe and possess unknown lands. Keeping these tropes in mind, I refuse to establish or clarify what I photograph in the city.

Early on in this work the India diaries of Allen Ginsberg, William Gedney and Alice Boner were my companion readings. They offer attentiveness to my own insider-outsider position: framed both by having lived away from the city for more years than I have lived in it, and by my female body which grafts me on the sidelines of the city’s social landscape, in spite of my cultural fluency.

Artwork courtesy sepiaEYE Gallery

Artwork courtesy sepiaEYE Gallery