Gallery Supplement

Throughout history, immigrants from around the world have been attracted to American citizenship and its promise of equal opportunity. And throughout history, newcomers to America have been granted or denied citizenship on various grounds, based on the color of their skin, their national origin, their perceived potential to assimilate into American culture and the value of their potential contribution to the nation.

THE PROMISE OF AMERICA: 1790 – 1900

Sikhs and Hindus Who Are Employed in the Mills. (Source: Lockley, Fred — The Hindu Invasion, p. 591, May, 1907, Pacific Monthly)

Seamen, indentured servants accompanying their British masters, merchants and adventurers are men from India whose names appear on crew and passenger manifests of ships arriving in the United States during the 1700’s. Many stayed and adopted Western names. Little is known about them and their lives remain the untold story of Indian American history.

Most of the Indians who began to arrive in the U.S. in the late 1800’s were Sikh farmers from Punjab. They responded to recruiting efforts by Canadian and American companies and found jobs along the Pacific Coast as laborers in lumber mills, agriculture and railroad construction. Students came seeking higher education at American universities, and merchants came in search of business opportunities.

Parsee merchants at Ellis Island. (Source: http://www.gjenvick.com/Immigration/EllisIsland/1907-05-ALookAtSomeOfOurImmigrants.html)

A RUDE AWAKENING: 1900-1924

Although some of the early Punjabi arrivals had become successful farmers and obtained U. S. citizenship, large numbers of Sikh laborers lived lives of low wages, menial jobs and discriminatory living conditions. They, along with other Asians, were treated with hostility and viewed as threats to the economic well-being of the established citizenry.

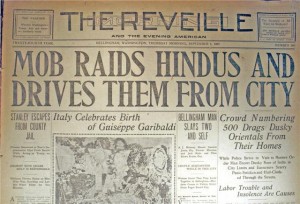

Anti-immigrant fervor began to turn violent.

Organizations such as the Asiatic Exclusion League (AEL) targeted Asian businesses for harassment and applied political pressure to keep out the “tide of turbans.”

The AEL blamed the “filthy and immodest habits” of the South Asians and their willingness to work for low wages as the cause of the mob violence that swept lumber towns in Washington State in 1907. The League monitored and publicized the voting records of legislators, published figures overstating the number of Asians in California and launched media campaigns against immigration officials, judges and legislators it felt were too sympathetic to Asians.

BARRING THE DOOR: 1917 – 1924

The 1790 Naturalization Act was the first of many laws passed with respect to citizenship. Laws aimed at Chinese and Japanese immigrants followed in the 1800’s. State and federal legislatures and the judiciary now responded to rising anti-Asian sentiment with further restrictive measures. Indians, along with Latinos, Chinese, Japanese, and Filipinos, were seen as a threat to the economic security and cultural cohesiveness of whites, and were targeted through judicial and legislative means for discrimination and exclusion.

The Immigration Act of 1917 prohibited Asians in the Barred Zone from entering the United States. In effect, immigration from India and other Asian countries came to a stand still and any hopes the early immigrants had of sending for their wives and children were dashed to the ground.

Other anti-Asian measures followed. As persons ineligible for citizenship, they were not allowed to own land, and the Cable Act of 1922 revoked the U.S. citizenship of women who married them. The Cable Act was eventually repealed in 1936, but for early immigrants from India the barriers to citizenship and equal rights remained.

With railroad construction completed, many Sikhs had turned to farming, their traditional occupation in Punjab. They worked around the 1913 California Alien Land Law which prohibited their ownership of land, by leasing property that they farmed. Such leasing was banned in 1920. By this time they had developed a reputation as excellent, hard working farmers, and they entered into partnerships with white farmers who were more than happy to reap the benefits of association with these immigrants.

BECOMING AMERICAN

Access to citizenship was a tool to address prevailing socio-economic concerns, a reflection of the personal sentiments of ruling judges and also an instrument of U.S. government foreign policy.

Whenever immigrants from India sought to establish themselves as American citizens, they found themselves at the mercy of the judiciary’s idiosyncratic interpretations of their eligibility. The lower courts played a large role in distilling the notion of Caucasian, Mongoloid, and Asiatic to suit their own agendas and to determine naturalization cases that affected Indians and other Asians.

Often, relatively dark-skinned Indians who cited their higher caste status or an aristocratic background were declared white and granted citizenship and its attendant rights.

Just as often, others were not.

The decisions varied depending on the location of the court hearings, the attitudes of the judges and the agenda of the government at the time.

The fight for independence for India and the fight for civil rights for Indians in America had been closely linked since the early 1900’s: the Chinese and Japanese immigrants, as citizens of independent, established nations, could turn to their homeland governments for protection. Their governments intervened on behalf their citizens in America and obtained restitution for damages they had suffered at the hands of mobs and anti-Asian vandals. The British government, however, did nothing on behalf of the Indians.

Indian independence movement activist Agnes Smedley sought support for Bhagwan Singh and other Indians who were under orders of deportation.

Indians in America were not only immigrants subject to discrimination and deemed ineligible for U.S. citizenship, they lacked the support and backing a strong and independent native land would provide its citizens. Further, according to the Civil Rights Act of 1866, “all persons born in the United States, and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the United States.” Therefore, many Indians in the U.S. believed a free India would strengthen their position in the United States. They took an active role in the struggle for India’s independence from Britain (an ally of the United States), and many had what the U.S. government considered radical views on individual freedom.

Because of their activities relating to freedom for India, several Indians were denied U.S. citizenship and several were deported.

THE LINE BETWEEN DAYLIGHT AND DARKNESS

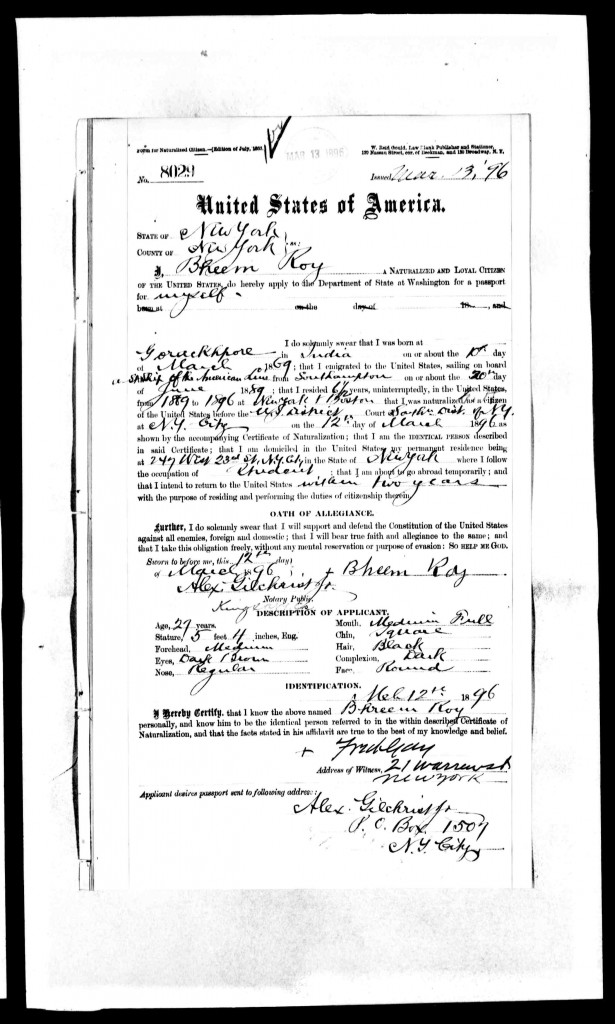

Although A. K. Mozumdar is often referred to as the first U. S. citizen of Indian origin, naturalization records indicate otherwise. Manak Bamji became a citizen in 1899, shortly before his graduation from Harvard Medical School.

Student Bheem Roy’s application for a U. S. passport indicates he was naturalized even earlier, on March 12, 1896. And India-born Moses Ibn Faraj Reuben became a citizen in 1888.

Whether the seamen, servants, merchants and adventurers who were among the first Indians to arrive in the U. S. applied for citizenship, and whether they were accepted or denied, remains a subject for further research.

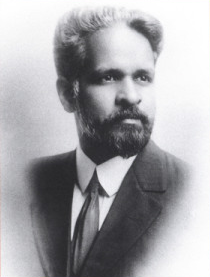

A. K. Mozumdar was initially denied citizenship in 1912 because he was not white. His lawyer, Sakharam Ganesh Pandit appealed the decision on the basis of Mozumdar’s high caste.

In the 1913 decision which made him among the earliest Indians to receive U.S. citizenship, District Judge Rudkin admitted the difficulties he faced:

“The difference between daylight and darkness is apparent to all, but where is the dividing line, and where does daylight end or darkness begin? So it is with the races of mankind….”

The table below reflects the confusion of the courts in implementing a race-based citizenship policy:

| Case | Holding | Rationales |

|---|---|---|

| In re Balsara, 1909 | Asian Indians are probably not White | Congressional intent |

| U.S. v. Dolla, 1910 | Asian Indians are White | Ocular inspection of skin |

| U.S. v. Balsara 1910 | Asian Indians are White | Scientific evidence Congressional intent |

| In re Akhay Kumar Mozumdar, 1913 | Asian Indians are White | Legal precedent |

| In re Sadar Bhagwan Singh, 1917 | Asian Indians are not White | Common knowledge Congressional intent |

| In re Mohan Singh, 1919 | Asian Indians are White | Scientific evidence Legal precedent |

| In re Thind, 1920 | Asian Indians are White | Legal precedent |

| U.S. v. Thind, 1923 | Asian Indians are not White | Common knowledge Congressional intent |

| U.S. v. Akhay Kumar Mozumdar, 1923 | Asian Indians are not White | Legal precedent |

| U.S. v. Ali, 1925 | Punjabis (whether Hindu or Arabian) are not White | Common knowledge |

| U.S. v. Gokhale, 1928 | Asian Indians are not White | Legal precedent |

| Wadia v. U.S., 1939 | Asian Indians are not White | Common knowledge |

| Kharaiti Ram Samras v. U.S., 1942 | Asian Indians are not White | Legal precedent |

| In re Najour, 1909 | Syrians are White | Scientific evidence |

| In re Mudarri, 1910 | Syrians are White | Scientific evidence Legal precedent |

| In re Ellis, 1910 | Syrians are White | Common knowledge Congressional intent |

| Ex parte Shahid, 1913 | Syrians are not White | Common knowledge |

| Ex parte Dow, 1914 | Syrians are not White | Common knowledge |

Source: Lopez, Ian Haney. White By Law: The Legal Construction of Race. New York: New York University Press, 1996.

THE WHITE REQUIREMENT: 1923

When the Bureau of Naturalization appealed the court’s 1920 acceptance of Bhagat Singh Thind’s citizenship application, lawyer Sakharam Ganesh Pandit was confident his client would be approved.

In Takao Ozawa v. United States, the court had ruled that the light-skinned, Westernized, Ozawa was ineligible for U.S. citizenship because as a Japanese person, he was not Caucasian. The key requirement appeared to be that applicants had to be Caucasian, and Indians had always been so classified by anthropologists and scientists. A year later, in 1923, the same court now denied Thind citizenship because though Caucasian, he belonged to a group not “commonly perceived as white.”

After the 1923 Thind decision, the government began revoking the citizenship of Indians who had already become U.S. citizens. Seventy Indians were denaturalized and the process of stripping citizenship from the rest began. Indians with ties to the Indian independence movement were among the first to be notified of their denaturalization.

Taraknath Das, one of several figures actively working on the twin causes of freedom for India and the right to U.S. citizenship for Indians in America, was a prime target.

He was already under surveillance at the request of the British government for his activities on behalf of Indian independence. Along with Har Dayal and other activists, Das in the early 1900’s had advocated armed rebellion against the British. By the 1920’s he had adopted a less radical approach and had begun to work within the American system, developing political networks and links to strengthen support for the cause. Das was denaturalized and as a result his American wife, Mary, a co-founder of the NAACP, lost her citizenship.

Denying her application for a U. S. passport, a State Department official advised her to get a divorce. For women denaturalized by the Cable Act, divorce or widowhood were the only paths available to regain their U.S. citizenship, unless they found another country who would accept them as citizens. Mary remained stateless till her citizenship was restored.

Sakharam Ganesh Pandit (Source: East Indians In America, Wendy Aalgaard)

Akhoy Kumar Mozumdar’s citizenship, initially denied, then granted, was now rescinded. He appealed the denaturalization and was represented in 1923 by Sakharam Ganesh Pandit, the lawyer who had initially argued his case and won him his citizenship. This time, however, Pandit was unsuccessful and Mozumdar’s denaturalization was upheld. Pandit was rebuked by the judge for his public criticism of the Thind decision, and the Justice Department then began proceedings to denaturalize Pandit as well.

1903: Arrives in Seattle, Washington. Learns English, and by 1906, develops a following as a spiritual teacher.

1912: Citizenship denied: Not White.

1913: Citizenship awarded: Caucasian of high caste. In granting Mazumdar citizenship, the presiding judge admits that distinctions within the Caucasian category were not clear.

1923: Citizenship revoked: Caucasian, but not white as per Bhagat Singh Thind Supreme Court decision.

1924: Revocation upheld.

1950: Reapplies for and wins citizenship.

Vaishno Das Bagai’s 1928 suicide by gas poisoning in his San Jose, California apartment was a graphic indication of the sense of desperation and betrayal among the Indians of the time. A staunch supporter of freedom for India, and eager for the freedom and the opportunity promised by America, he had arrived in 1915 with his family.

In spite of his relative prosperity, he had come to realize that the reality of life in America was a far cry from the ideals professed by the nation. He saw colleagues in the Indian freedom movement placed under surveillance, arrested and deported, and the discrimination endured by his fellow countrymen at the hands of the law and society.

He had renounced his British citizenship in support of India’s independence. His denaturalization rendered him stateless.

The desire and the right of established citizenry to shape the nation’s form and content was, once again in its history, clearly at odds with its founding principles.

DALIP SINGH SAUND

(Source: http://www.pbs.org/rootsinthesand/ images/)

The Dalip Singh Saund story exemplifies, in one man’s life, the challenges overcome by early Indians. Saund had arrived in the United States in 1920 and received a doctorate in Mathematics from the University of California at Berkeley in 1924.

As an Indian he was limited in his choice of occupations, gave up his attempts to find a job as a teacher and became a lettuce farmer.

“Even though life for me did not seem very easy, it had become impossible to think of life separated from the United States… The only way Indians in California could make a living at that time was to join with others who had settled in various parts of the state as farmers.”

Anti-Indian prejudice was a consistent presence during his early life in America. His wife lost her U.S. citizenship because of the Cable Act. He himself was finally able to become a citizen in 1949.

When citizenship became available again in 1946, early Punjabi pioneers all over California applied and became citizens. With a Hispanic campaign manager, a white voter base and the support of the Punjabis, Saund was elected to Congress in 1956 and represented California’s Imperial Valley for three terms.

THE TIDE TURNS: THE MOVE FOR INCLUSION: 1924-1946

The earlier revolutionaries had failed to win the sympathies of the American public because of their radical tactics. With the new activists who began arriving on the East Coast in the 1920’s, efforts were directed instead, to educate the public, and at the same time, forge links with important organizations, other disadvantaged groups, as well as influential and powerful individuals.

| Key Figures N. R. Checher Syud Hussain Mubarak Ali Khan Chaman Lal Haridas Mazumdar Krishanlal Shridharani |

Clare Booth Luce R. Emmanuel Celler S. Everett Dirksen S. William Langer R. Lesinski Anup Singh J. J. Singh |

Key Organizations India Welfare League Indian Association for American Citizenship Indian National Congress Association of the West Coast National Committee for India’s Freedom Research Bureau of the India League India League of America Indian Chamber of Commerce |

During the 1944 hearings on Senator William Langer’s bill to allow naturalization rights for Indians already in the United States, the counsel for the Indian Association for American Citizenship introduced a list of Indians including “some very prominent scientists who have contributed a great deal toward the progress of this country” who were ineligible for citizenship. The list included:

- Dr. S. Chandrasekhar: Professor of Astronomy and subsequent Nobel laureate

- Dr. Saklatwalla: Mineralogist and president of United States Rustless Steel Corporation

- Dr. V.R. Kokutnur: chemical engineer and Captain in the U.S. Army

- Dr. Subbarao: Biochemist, Director of Research at Lederle Laboratory

- Dr. Gobind Behari Lal: Scientist, journalist and Pulitzer Prize winner

- Dr. A. K. Coomaraswamy: Curator of the Boston Museum

— From Sikhs, Swamis, Students and Spies, Harold A. Gould

THE NEW AMERICAN

Indians gained the right to citizenship in 1946, and since then, they have continued to enter the United States in large numbers to satisfy the nation’s need for workers and to fulfill their own personal and family aspirations. The government has opened many paths to citizenship for those immigrants it values enough to include as permanent members of the nation.

In a transnational world, a citizen’s allegiance to the state is part of a complex mosaic of economic, family, cultural, and religious loyalties. For Indian Americans, whose love for America coexists with their strong loyalty to family and attachment to India, their American citizenship has become a way to bring family together and promote friendship between native country and adopted homeland.