ACROSS THE NATION

INDIAN FREEDOM FIGHTERS IN THE UNITED STATES

Lajpat Rai’s speeches and writings helped improve the American public’s understanding of India. (Source: Open Library, first published in 1919)

While the Gadarites advocated armed rebellion, other activists in the United States were taking a different route in seeking independence for India. The Quakers, inspired by Swami Vivekananda’s 1893 address at Chicago’s World Parliament of Religions, were among the American groups supporting the cause. With established public figures and academics at their helm, American organizations such as the New York-based Society for the Advancement of India founded in 1907 also furthered the cause.

Other activists linked fair treatment of immigrants with the issue of Indian independence. Salindranath Ghose and Agnes Smedley, a student of Indian leader Lala Lajpat Rai and a Socialist with a passion for liberation from imperialism, organized Friends of Freedom for India (FFI). They drew support from the Industrial Workers of the World and the Socialist Party to lobby for the rights of immigrants to engage in political activity. Even the historically anti-immigrant American Federation of Labor, with Samuel Gompers at the helm, endorsed the FFI’s mission. The FFI also consolidated earlier links with Irish Americans seeking to oust British rule in Ireland. The influential Gaelic American extolled India’s independence movement, Irish Republicans lobbied alongside the FFI, and the main 1920 St. Patrick’s Day parade featured Irish hero Eamon de Valera and the FFI front and center.

Women who made important contributions to the Indian freedom movement included triple agent Agnes Smedley. “Agnes Smedley in Sari” 2009. Online image. (Source: Punjabi Research Group)

After his arrival in 1914, Lala Lajpat Rai recognized that in the U.S. criticizing the British would be viewed as being pro-German. He distanced himself from the revolutionaries and anarchists. Touring the country, he built relationships with prominent leaders and influential thinkers, established links with the American civil rights movement and held discussions with luminaries such as W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. He established the India Home Rule League Society of America in 1917 and the India Affairs Bureau in 1918, re-educating the wider society on Indian culture, philosophy and contemporary needs, and enlisting their support on the issue of home rule for India.

Illinois Senator Joseph McCormick became the first senator to condemn British rule in India in an address to the Senate in August 1919.

Other organizations built upon these efforts and garnered further support for an independent India. They included the Indian Welfare League, founded in 1937 by Mubarak Ali Khan, a successful farmer in Arizona who came to the US in 1913, as well as the India League of America, whose president in 1940 was Sardar Jagjit (“J. J.”) Singh.

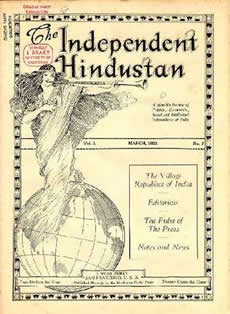

The Independent Hindustan was published by the Gadar Party in 1920-21 in cooperation with Friends of Freedom for India and reflected the party’s shift from advocating armed rebellion to support for Home Rule.

One can only imagine the stunning visual impact of the 6-feet tall, turbaned Singh, who arrived in the U.S. in 1926 to operate India’s concession at Philadelphia’s Sesquicentennial Exposition, ran out of money and stayed on. He was a handsome, charismatic merchant whose wealthy clientele wielded great influence and power. He was remarkably effective in persuading public and politicians alike that expanded trade and business opportunities would come from India’s political freedom. He held frequent press conferences as well as lavish dinner parties and events at prestigious hotels, where he made sure a well-known public figure or two would be present to attract attention. He worked hard, walking for miles through the corridors of Congress, and courted key leaders so effectively that throughout the country, he was known as the “One Man Lobby.”

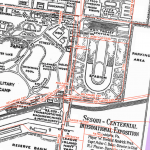

At the Sesquicentennial Exposition celebration of 150 years of American independence, J.J. Singh, later known as the “One Man Lobby,” ran the Indian pavilion of London’s Taj Mahal Trading Company. Source: Phillyhistory.org

The India pavilion was located south of FDR park at Pattison Avenue and Broad Street in Philadelphia.

Congresswoman Clare Boothe Luce was one of his many supporters, and through her influence, Time magazine, published by her Anglophile husband Henry Luce, softened its stance on the Indian nationalists.

Foreshadowing developments decades into the future, Singh declared in a 1945 statement he made before the U.S. Congress: “The 400 million East Indians represent a great untapped trade reservoir. There exists over there a great demand for American goods.” As head of the India League of America, J. J. Singh continued to work for good relations between India and the United States and was a key figure among Indians in America fighting for the right to U.S. citizenship. (For more information, click here to visit NIAM’s gallery “The Struggle for Citizenship.”)